In 2019, at the request of the Data Iwi Leaders group, Stats NZ commissioned a report outlining the benefits, risks, and mitigations of storing iwi and Māori data in the cloud.

Offshoring New Zealand Government Data Report [PDF 949KB]

We have been engaged by Statistics New Zealand – Tatauranga Aotearoa (Stats NZ) to undertake an engagement process with certain Māori individuals and organisations and develop a report that comprehensively outlines perspectives on the benefits and risks of both onshore and offshore data storage through a Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Te Tiriti) and Te Ao Māori (Māori worldview) lens.

In July 2019 the Government Chief Data Steward, on request from the Data Iwi Leaders Group (the Data ILG), agreed to produce a discussion paper identifying the risks (and setting out how risks are being managed) in relation to the storage of Māori data held by agencies across the public service, particularly with respect to cloud storage. A paper entitled Discussion Paper: Offshoring New Zealand Government Data (the GCDS Paper) was subsequently produced by the Government Chief Data Steward (the GCDS) and provided to the Data ILG for feedback.

Following their review, the Data ILG technicians indicated that they were not able to support the GCDS Paper in its current form. They considered that there was a need for a more balanced and in-depth appraisal of the issues. In particular, they recommended that the following were incorporated into the next version of the paper:

Accordingly, we were engaged by Stats NZ to:

A key element of the work that we undertook was engaging, with staff from Stats NZ, with certain Māori individuals and organisations (who we have called Māori interviewees). The Māori interviewees were selected by Stats NZ based on their previous experience or expertise in relation to Māori data kaupapa (whether direct or indirect). We also spoke to personnel from Stats NZ, the Department of Internal Affairs, and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The information obtained from those interviews was supplemented by written feedback from a number of agencies within, or connected to, the Government Information Group (the GIG respondents), and by other written material.

It is important to acknowledge that the Māori perspectives referred to in this report are a limited sample of perspectives, elicited from the Māori interviewees that we engaged with and the written materials that we considered. While the report does explore, on a high level basis, certain perspectives identified from the points of view of the Māori interviewees, it does not represent a definitive account of all Māori perspectives on this subject. A much wider engagement exercise would need to be undertaken (in a culturally appropriate manner) to obtain a more in-depth understanding of the Te Ao Māori perspective on data storage.

This report also references some of the analysis of an earlier draft version of this report by Dr Chris Culnane and Associate Professor Vanessa Teague in a paper that was independently commissioned by the Data ILG in February 20213 (the Culnane Teague Report) as that analysis relates to the pros and cons of onshore and offshore cloud-based data storage. The Culnane Teague Report supplements, and to an extent contrasts with, the views expressed by GIG respondents.

The focus of this report is limited to onshore and offshore options for cloud-based storage of New Zealand’s government data – including Māori data – held by government agencies, and agencies’ decision making processes in respect of data storage. We have not been asked to consider how agencies make decisions regarding:

As explained below in section 2, there are potential limits to the utility of engagement focussed solely on data storage. The agencies that we surveyed not only used public cloud-based services for storage, but also used Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) and Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) solutions. These run on top of third-party infrastructure and, in the majority of cases, are hosted in offshore locations. The use of PaaS or SaaS solutions usually entails storing data in those platforms, or moving data to those platforms as required so that it can be processed or “worked on”. Agencies are therefore effectively making decisions on data location when procuring any cloud-based service, not just data storage services. Accordingly, if the government is to have a conversation with Māori around data location, there is a need to consider how agencies make decisions regarding the procurement and use of onshore and offshore cloud-based services more generally.

It is also important to note that this report does not:

Māori data governance is the focus of a series of wānanga (fora) facilitated by the Data ILG and GCDS (see section 2 below for some further background to this work). Accordingly, while consideration of Māori data sovereignty and Māori data governance are outside the scope of this report, we wish to highlight at the outset that:

Stats NZ has entered into a Mana Ōrite Relationship Agreement with the Data ILG, the purpose of which is for both parties to work together to realise the potential of data to make a sustainable, positive difference to outcomes for iwi (tribes), hapū (subtribes) and whānau (families). The agreement sets out a work programme which specifies certain agreed outcomes for the year. One of the agreed workstreams under the Mana Ōrite Relationship Agreement is for the parties to co-design a Māori data governance model. We understand that through this workstream, the parties intend to develop an approach to data governance that reflects Te Ao Māori needs and interests in data (which we discuss further below). The key focus of this report is the storage of Māori data held by the Crown and, as such, it does not focus on the wider concepts of Māori data governance. That said, we point out that there are overlaps between the matters dealt with in this report and the wider Māori data governance workstream that is currently underway.

There are also likely to be overlaps with the whole-of-government approach (referred to as “Te Pae Tawhiti”) to addressing the issues raised in the Wai 262 claim and the associated Waitangi Tribunal report Ko Aotearoa Tēnei. Wai 262 was a contemporary Treaty claim which focussed on, amongst other things, the protection of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge). The next phases of Te Pae Tawhiti will involve developing a whole-of-government plan of action, supporting Māori-to-Māori conversations about partnering with the Crown, exploring opportunities to raise the profile of the protection of Mātauranga Māori in international fora, and advancing opportunities for early progress.

The Māori data governance work that is underway is also potentially relevant to the Crown’s agreement to develop a national plan of action on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (the UNDRIP). The UNDRIP is discussed in more detail in section 6.

The key themes that we drew from the kōrero (comments) of the Māori interviewees and the relevant written sources are as follows:

Distinctly Māori perspectives exist in relation to data, including how it is stored, authenticated, transmitted and protected. We refer to the following examples provided by Māori interviewees in this respect:

Te Ao Māori perspectives can provide valuable insights into decision making processes in respect of Māori data (including in relation to cloud storage):

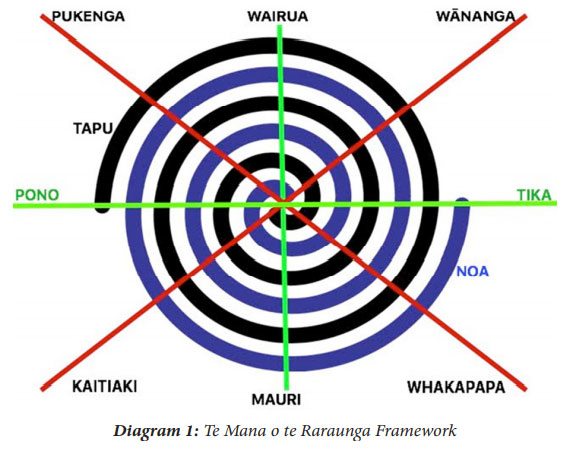

There is a lot of work currently underway by various Māori data experts (including the Data ILG and Te Mana Raraunga) to operationalise Te Ao Māori views within the government’s system of data governance, including in relation to the storage of Māori data held by the Crown. To this end, for example, Te Mana Raraunga, and people affiliated with Te Mana Raraunga, have developed conceptual frameworks for Māori data governance based on Te Ao Māori principles.

There are concerns in relation to the way that agencies currently make decisions about the storage of Māori data. Relevantly, these are:

There was a shared recognition amongst Māori interviewees that Māori data exists on a spectrum and that accordingly there is no single “rule” as to when Māori data should remain onshore or may be offshored. It appeared to us that the dominant concern of Māori interviewees was not with the substantive decision (i.e., to store data in an onshore cloud data storage solution or an offshore cloud data storage solution) but with the decision making process.

Related to the previous paragraph, to realise Māori aspirations in relation to data and improve trust and confidence in decision making, Māori should be involved in making decisions about the storage of Māori data.

Addressing the concerns of the Māori interviewees set out above (in relation to the way that agencies currently make decisions about the storage of Māori data) could, at a high level, be considered to be broadly in line with agencies’ obligations pursuant to Te Tiriti. We have set out in section 6 below a high level analysis of legal considerations that agencies may wish to take into account in making decisions about data storage.

Insofar as Stats NZ is concerned, addressing these concerns is also consistent with the Mana Ōrite Relationship Agreement that it has entered into with the Data ILG. The key idea behind the Agreement is recognition that the parties have equal “explanatory power” – that is, they acknowledge and accept each other’s unique perspectives, knowledge systems and world views as being equally valid to decisions made under the relationship established by the Agreement. Stats NZ has committed under the Agreement to “work[ing] across the public sector data system to improve access to data and increase opportunities for iwi, hapū, whānau and representative Māori organisations to engage and have input into decisions on future system and data design”.

Other key features of the Mana Ōrite Relationship Agreement are:

A set of defined goals for the relationship, including that:

A set of relationship principles, which both parties agree to honour in the conduct of the relationship. Those relationship principles are as follows:

The parties acknowledge that the Agreement is in addition to, and not a substitute for, the broader relationship between Māori and the Crown, and does not replace the primary Tiriti relationship for individual iwi between the Crown and its representative Minister in the relevant context.

While the Mana Ōrite Relationship Agreement is between Stats NZ and the Data ILG (rather than other agencies and/or iwi or other Māori groups) – and is fundamental to that relationship – agencies may wish to consider it as a good example of operationalising the Treaty relationship between the Crown and Māori groups, and what a model for shared decision making might look like.

The key themes that we obtained from the written responses of the GIG respondents are as follows:

Various GIG respondents expressed a desire to address Māori concerns in relation to the Crown’s current system of cloud storage adoption decision making. As a practical example of this, some GIG respondents have paused their cloud procurement decisions pending the provision of clear guidance on the circumstances in which Māori data may be offshored.

GIG respondents stressed the need for any new framework relating to cloud storage adoption decision making to be:

At a practical level the GIG respondents referred to a need for any new framework to:

At a high level, the Māori interviewees and GIG respondents appear to share a common desire to work together on this kaupapa. Therefore, an opportunity exists for the parties to develop a meaningful way forward which is consistent with Māori aspirations, and builds trust and confidence in the Crown’s decision making processes.

In light of the above, we have suggested that Māori and agencies could work together to co-design a framework, to be used by all agencies, to facilitate a weighing-up of the risks and benefits of offshoring on a case-by-case basis. We have provided, in section 11 below, some suggestions for different ways in which such a framework could be designed. Whatever approach is adopted, we consider that ideally a data storage framework would work together with other frameworks, or form part of an overall cohesive strategy. That is, we consider that it should acknowledge existing kaupapa Māori frameworks and should align, to the extent possible, with the Māori data governance framework that comes out of the wānanga being facilitated by the Data ILG and the GCDS.

As requested by Stats NZ, we have also separately provided some guidance that could be adopted for use by agencies as an interim aid to support decision making about where to store Māori data when using cloud-based data storage services. The request for interim guidance is motivated by the fact that, while there is broader work being undertaken in relation to Māori data governance, including co-design of a Māori data governance framework, agencies wish to ensure that they are considering Treaty principles when making decisions now about whether to use an onshore or offshore cloud-based data storage service.

As discussed in the remainder of this report, a key concern raised by Māori is about the process by which agencies develop policy and make decisions in relation to Māori data. That is why we suggest that Māori and agencies should co-design a framework that assists with decisions to offshore data. It is also why we consider that any guidance that we provide should only be used as an aid in decision making on an interim basis. We are of the view that if the Crown wishes to improve trust and confidence in its capacity and capability to act as a steward in relation to Māori data, it will need to engage with Māori in policy design and involve Māori in decision making in this area.

The remainder of this report:

In this section we highlight those areas that are not directly within the scope of this report and their relevance to concerns about data location and how data storage decisions are made.

We also:

The focus of this report is on onshore and offshore options for cloud-based storage of New Zealand’s government data, including Māori data, held by agencies. We have not been asked to consider how agencies make decisions regarding:

However all agencies surveyed are not only using public-cloud based services for storage but are also procuring PaaS and SaaS services, which, in turn, run on top of third party infrastructure. In the majority of cases these PaaS and SaaS services are hosted in offshore locations. When agencies procure PaaS and SaaS services, they are:

For these reasons we consider that the distinction between straight storage (or infrastructurelevel) services and Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) and Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) is somewhat artificial. We also note that Māori interviewees were not making this distinction in the course of their comments on the offshoring of Māori data.

One GIG respondent observed: “The idea of datacentres hosting an application or data is gradually becoming obsolete as software vendors seek to offer ‘platform or software as a service solutions’ to drive efficiency, ease of use and performance.”

Accordingly, agencies are effectively making decisions on data location when procuring any cloud-based service, not just data storage services.

If the government is to have a conversation with Māori around data location, there is a need to consider how agencies make decisions regarding the procurement and use of onshore and offshore cloud-based services more generally. In our view the legal concepts discussed in section 6 of this report would be applicable to decision making by agencies in relation to the procurement of both cloud-based data storage services and cloud-based services more generally.

In addition, this report does not seek to define “Māori data” or the wider concepts of Māori data sovereignty and Māori data governance.

While the level of concern amongst Māori interviewees around the specific question of data location varied somewhat, the common response by Māori interviewees was a desire to:

This is the much broader subject of Māori data governance, which was the focus of the co-design wānanga facilitated by the Data ILG through its mahi (or operational) arm, Te Kāhui Raraunga Charitable Trust (Te Kāhui Raraunga), and the GCDS in 2020. We expand on this below.

The Māori data governance co-design wānanga were an output of the work plan developed under the Mana Ōrite Relationship Agreement which was entered into between the Data ILG and Stats NZ in October 2019. We understand that the primary purpose of the wānanga was to “co-design a system-wide model for Māori data governance to ensure data design, collection and dissemination serves iwi and Māori needs and aspirations”.20

The co-design wānanga were led by Te Kāhui Raraunga, with support from wider Data ILG personnel and Stats NZ. Participants were iwi and national Māori leaders, representatives of Māori organisations with data interests, individual Māori data experts, and senior representatives from 16 government agencies.

The co-design wānanga process started in August 2020 with working wānanga for a subset of both the ao Māori and kāwanatanga (government) participants in preparation for the two co-design wānanga. The two co-design wānanga took place in September and October 2020 in Wellington.

We understand that the key outcomes from the co-design process were as follows:

The majority of GIG respondents made express reference to, and expressed their intention to be guided by, the outcomes of the Māori data governance co-design wānanga. A number of GIG respondents also referred to Māori data governance initiatives that they have implemented, or are in the process of implementing, in their respective areas.22

The relevance of these broader questions is that Māori interviewees saw a linkage between decision making processes regarding data storage and Māori data governance more generally. It was observed that working out how decisions regarding data onshoring and offshoring are made “is just a subset of the working out what the whole Māori data governance system should look like and what represents a ‘robust’ system”.

For this reason, while Māori data sovereignty and Māori data governance are outside the scope of this report, it is important to highlight the need (referred to in section 11) for any new decision making framework to align with the Māori data governance framework that comes out of the co-design wānanga.

The ability to identify and classify Māori data is central (and a necessary precursor) to any informed decision making regarding where data is stored. Only when agencies know what data they have can they make decisions about it – not just where to store it, but for how long to store it, who should have access, how they should have access, and the level at which it should be secured.

Most GIG respondents acknowledged the need for this and viewed it as a challenge. The challenge is complicated by the fact that data tends to some degree to be held in silos and decision making also occurs in silos. The government has many distributed (significant) data sets, with Māori data (structured and unstructured) seeded right throughout them. The government currently relies on a security classification approach in order to determine what data may be offshored (referred to in sections 4 and 5 of this report). This approach does not enable a matrix classification – that is, to take a large data set and identify different elements within that data set as having varying levels of sensitivity when measured or assessed from a range of perspectives (including significance to Māori).

Māori interviewees saw the development of an information management classification system, to enable identification and to manage access and use, and metadata classifications (data about the data), as key. One Māori interviewee commented:

"Labelling, which provides the context about the information, is just as important as the information itself – it limits what can be accurately inferred from the data/what decisions can be made based on that data. Without labels information can just get lost. Just giving people access is not enough."

Another Māori interviewee stressed the need to have people who can contextualise the data before other decisions are made about it.

At an even more fundamental level there is a need for common metadata standards for people:

"Māori people are just people too. People first, a cohort second. Get that right and then there’s a more overt cultural construct that you can lay over the data. If we have the latter but then apply it in 20 different ways because we don’t have the former then we are back to square one."

Some significant thinking has already gone into how to define Māori data.

Te Kāhui Raraunga has produced a paper setting out guidance for Stats NZ and other government agencies on the needs for and uses of iwi data. That paper defines Māori data as “data that is about Māori; data that is from or by Māori; and any data that is connected to Māori”. The rationale for that expansive definition is explained as follows:

Our earlier wānanga about data sovereignty resulted [in] the following definitions for Māori data:

As such, we consider iwi data to be any data of this nature: data that is about Māori; data that is from or by Māori; and any data that is connected to Māori. This includes data about population, place, culture, environment and their respective knowledge systems. In our view, this spectrum can be both quantitative and qualitative data, and therefore include any data or information that comprises iwi knowledge systems, whether implicit and encoded in cultural items such as karakia, haka, waiata tawhito and pakiwaitara; or explicit in terms of statistics and qualitative narratives. It is not just statistics.

We understand that methodologists often want concepts to be practical and have clear and bounded definitions. However, for us data underpins how we use data for governance, for mana motuhake, for tino rangatiratanga. If we limit this definition further, then the data ecosystem will continue to be designed against our data needs, and we will not have the appropriate data for our own governance.

Using the lens of data governance, we assert control over this data according to the principles of relevance and access … . Secondly, the breadth of Māori and iwi data should be seen within the context of data for governance. While this definition is expansive, it is easier to understand why it is this broad if readers understand that “data that affects Māori in any way” refers to iwi and Māori desires and aspirations to exercise tino rangatiratanga for our own governance purposes.

In accordance with Stats NZ’s instructions, we have adopted this definition for the purposes of this report.

We note that the definition of Māori data provided by Te Mana Raraunga is similar (although refers to the data being “digital or digitisable”). That definition provides as follows:26 Māori data refers to digital or digitisable information or knowledge that is about or from Māori people, our language, culture, resources or environments.

In light of the breadth of these definitions it is not surprising that a number of Māori interviewees view Māori data as existing on a spectrum: “On that spectrum are things that we would be incredibly upset if it is out of our control and mana [authority] and if it went anywhere. But at the other end are things that we might want to sell.”

Some GIG respondents also acknowledged that particular data sets stand out – for example, iwi data holdings around whakapapa (genealogy), major statistical indicators for iwi, and health data – acknowledging that these require particularly careful management.

In section 6 of this report we discuss the relevance of classification to the application of Treaty principles, and what this means for decision making by agencies.

All Māori interviewees were clear that Māori must be part of the decision making process when deciding how to classify Māori data. Some Māori interviewees thought that the basic approach for developing a system for classifying Māori data should be the same as the process for developing a protocol or framework for making decisions about offshoring of Māori data. Once the standards are in place, an assessment or screening tool could be developed around this and deployed to classify data. One Māori interviewee thought this should logically be a digital tool for a digital problem.

We set out in section 11 of this report some suggestions on how a framework for classification of Māori data could operate in combination with a decision making framework regarding the storage of that data.

Some GIG respondents pointed to specific examples of data sets that have been identified as Māori data, or to work underway to identify data sets that could be classified as a taonga. For example:

Some Māori interviewees referred to a range of rights and interests that apply in relation to Māori data – legal rights through to inherent cultural, indigenous and human rights. However traditional legal concepts of property are of limited use when conceptualising rights in relation to data. There is no legal owner of raw data because copyright does not subsist in that data, although copyright can subsist in compilations of data and in insights derived from that data.

Overseas there are some models where interests in data are seen by indigenous peoples through the lens of ownership.30 While we consider that these models are not currently of direct relevance in New Zealand (given our existing legal framework and in light of Treaty jurisprudence in other contexts, which focusses on authority and control rather than ownership and possession), they are briefly discussed in section 6. As set out there, we do not discount the possibility that concepts of ownership may become relevant as part of the broader work being carried out in relation to Māori data governance.

We understand that Te Mana Raraunga is also currently giving some thought to what comprises an indigenous right in relation to data – not a right in the sense of an ownership right but a range of rights, such as the right to use and the right to prevent or control use by others.

Accordingly, for these reasons, we do not refer in this report to “ownership” of Māori data that has been collected and is held by agencies. We suggest that it is more helpful to think about the multiple rights that exist in relation to data, and suggest that any decision making framework relating to the offshoring of this data ought not be premised on the assumption that the data in question is “owned” by one Treaty partner or the other, but that each Treaty partner will have various obligations, rights and interests in relation to that data.

This section of the report sets out some perspectives provided by Māori interviewees on the specific question of data location, and outlines some of the particular contexts in which certain of the Māori interviewees are using, or their clients are using, cloud storage services (including Māori Television’s current content storage arrangements).

Some Māori interviewees referred to an awareness of a general sentiment that all Māori data held by government should stay in Aotearoa and that the Crown should have to make the case for why that data should leave Aotearoa. However, all Māori interviewees acknowledged that Māori data exists on a spectrum and that some data is more sensitive than other data. A recurring theme of the interviews was that cloud storage decisions should be made on a case by case basis.

There was a view expressed by some Māori interviewees that as soon as Māori data goes offshore there is a loss of control over such data.31 Interviewees observed:

It was clear from the kōrero with Māori interviewees that underpinning stated concerns regarding location is the more fundamental concern of regulating access and use (i.e., control) of the data. Whichever third party cloud storage solution is selected, there is still the same need to ensure ongoing access so that Māori can utilise the data for their own purposes. The need for, and methods of enhancing, Māori control over data are discussed further in section 8 of this report.

Some Māori interviewees emphasised that the decision whether to offshore data should involve discussion of the benefits as well as the risks. A benefits discussion should cover what is not being obtained in terms of the ability to analyse, interpret and extract value from the data in question by retaining the data onshore:

The narrative that is missing is what are the [benefits] of storage of data offshore and what are the protocols to ensure that we can unreservedly say that we will always have access to it. It may be that we need back-up copies locally.

A key observation by one Māori interviewee was that if Māori are not involved in the decision making process then the point of focus will become the substantive decision. However, if the right decision making frameworks and processes are in place, then there is potential to be agnostic (depending on the sensitivity of the data) about whether the data is stored onshore or offshore. This was a consistent theme of the interviews, and is discussed further in section 8 of this report.

It is important to recognise that the decision does not need to be binary – that is, simply between offshore cloud storage and onshore cloud storage. The majority of Māori interviewees were explicit about the need to ensure that a range of cloud data storage solutions are, and remain, available to government agencies, including hybrid options, so that there are ways of mitigating some of the jurisdictional issues. Commentary on the ongoing requirement for hybrid storage solutions is set out in section 12 of this report. As one interviewee phrased it, instead of endeavouring to “design” the problem to fit the solution, the government should ensure that there are a range of possible solutions on offer.

Digital Navigators Limited is a services company providing GIS, mapping, and strategic digital technology consultancy services to iwi and indigenous communities – to assist in the collation of data from indigenous knowledge systems and mapping/cross-referencing of that data against government geospatial data. Iwi clients are both large and small with varying resources and digital capabilities and are using a range of onshore and offshore storage solutions, including (in the case of the larger iwi) Amazon Web Services (AWS).

Āhau.io is a technology company that has built digital tools to enable whānau-based communities to capture important information, histories and narratives in community archives and to store and share that data using infrastructure that is controlled and managed by the people. The experience of Āhau is that people do care about storage location and that there is concern over jurisdiction. Some groups store their archives on local devices. One rōpū (group) who worked with an offshore storage provider specifically selected Canada over the US to store its mātauranga (history, whakapapa).

One Māori interviewee referred to a data storage project that he was actively involved with in the Far North (as at the time of the kōrero). This related to the storage of kōrero tuku iho in respect of a grouping of papakāinga in Hokianga. The kōrero tuku iho is currently stored in an on-premise storage system at one of the kura (school) embedded in the papakāinga community. As the kōrero tuku iho is inherently linked by whakapapa to the community’s tūpuna (ancestors), the data contained within it was perceived as particularly important and in need of protection from interference (which, in the Māori interviewee’s view, the onshore option ensured): “we don’t want people ‘tutu’ing’ around with our whakapapa... ever”.

At the time of our kōrero, papakāinga community representatives were engaging with Spark and other providers to investigate moving away from a traditional on-premise storage system to a local cloud solution. This was largely due to a desire to facilitate access to, and management of, the data by papakāinga whānau members. It was also a long term goal for the storage system to enable the exchange of indigenous knowledge with other indigenous communities throughout the Pacific and North America (e.g. the Navajo people). Māori video content provider: Māori Television

The empowering legislation for Māori Television41 acknowledges the Treaty partners’ joint obligation to preserve, protect and promote te reo Māori (the Māori language). The principal function of Māori Television is to “contribute to the protection and promotion of te reo Māori me ngā tikanga Māori [through the provision of the television service]”.

Māori Television took its protection function into account when it made a deliberate decision to use a local cloud-based service provided by Catalyst IT Limited for the storage of its website content. A Māori Television representative observed that Māori Television’s preference is to have this content “down the road” rather than in another country. Catalyst IT is a New Zealandowned company with three local data centres (in Porirua, Hamilton and Wellington). While a local cloud solution means higher storage costs and limited redundancy relative to an offshore cloud solution, moving large volumes of data offshore and then back onshore creates its own issues around latency and content transfer (in the form of access and restore times) that can then only be solved by purchasing more bandwidth, which comes at a significant additional cost. Accordingly, a local data storage solution makes sense from a range of perspectives.

In addition to the low resolution copy of each video file stored in Catalyst IT’s cloud, high resolution archive copies are retained on Māori Television’s premises and tape copies are stored at an off-site location in New Zealand.

The Māori Television representative explained that Māori Television’s core concern, however, is effective content access management. Access is carefully managed via terms of understanding with the “owners” of the content. We understand that while the “owners” are not told where content will be stored, a clear understanding of the purposes for which the content will be used is documented. Should Māori Television subsequently wish to re-purpose the data then it will go back to the “owners” and seek permission for such use. Particular care is taken with sensitive content, such as whaikōrero (pōwhiri oratory), tangihanga (funerals, rites for the dead), Waitangi Day celebrations, and coverage of controversial events such as the 2007 police raids in Te Urewera. In all these cases, specific terms of understanding are “wrapped around” the content.

This section of the report summarises:

The primary purpose of this report is to introduce a Te Tiriti and Te Ao Māori lens or perspective and to consider how this might be incorporated into the decision making frameworks used by agencies. Accordingly, we have not conducted any independent analysis of the pros and cons of onshore versus offshore cloud-based data storage solutions, and we have presented the perspectives of GIG respondents in summary format only.44

The table set out in Appendix 2: Current landscape: storage infrastructure service providers and location, shows the range of third party storage providers currently in use by GIG respondents, and which we expect is broadly representative of the public sector as a whole.

All agencies surveyed are using a combination of:

Some agencies continue to run their own legacy onshore capability, hardware and systems due, in part, to the prohibition on holding data above RESTRICTED in a public cloud (whether hosted onshore or offshore), although the extent to which these are used and where precisely they are located was not clear from the GIG responses.

In addition, all GIG respondents are procuring various SaaS services.45 The majority of these SaaS services are running on AWS or Azure infrastructure.

The table set out in Appendix 3: Pros and cons – offshore and onshore data storage solutions, has been populated on the basis of responses from GIG respondents. GIG respondents were asked to consider (amongst other things) the key risks to the ability of the Crown to perform its role as data steward or data custodian associated with the use of onshore data storage services compared to the services provided by Azure and AWS from offshore. This table does not reference the legal and broader “trust and confidence” issues associated with each option, which are the main focus of this report.

By way of summary, the onshore service providers and solutions do not appear to be viewed by the GIG respondents as providing the same levels of security, scalability, performance or resilience of the global hyperscale public cloud providers. One GIG respondent commented that:

"Assessment of security risk has shifted in the last few years, from a view that data was safest in our own data centres, to recognising that major public cloud vendors provide significant security benefits. This is particularly so when systems need to be accessible externally to enable effective delivery of public services."

Further, due to the economies of scale that can be reaped by AWS and Microsoft, the offshore options are widely regarded by GIG respondents as being more cost effective. Nor does AoG IaaS replicate the range of capabilities and functionality of a hyperscale public cloud provider like Azure or AWS, with one GIG respondent noting:

"Ultimately a disk is a disk for storing data, but it’s what you can do with that data [that matters]. To gain any benefit from onshore data organisations must create the capabilities themselves, which is far higher cost and lower quality [compared to the services offered by the offshore hyperscale public cloud providers]."

The GIG respondents were not asked to comment specifically on the third option of an onshore data storage solution operated by a company under foreign ownership.

The table in Appendix 3 also references some of the commentary from the Culnane Teague Report as this relates to the technical pros and cons of onshore versus offshore data storage solutions. The Culnane Teague Report supplements, and to some extent contrasts with some of, the views expressed by the GIG respondents.

In this section of the report we summarise current approaches to decision making by agencies. We have defined “jurisdictional risk” and summarised what GIG respondents and Māori interviewees have said about how jurisdictional risk is, or should be, factored into decision making by agencies. We then highlight the gaps in those existing decision making frameworks to the extent that these have been acknowledged by the GIG respondents and also as highlighted by Māori interviewees. We also note the actions that some GIG respondents are taking to incorporate a Māori perspective into cloud-based service procurement decisions.

Cabinet’s “Cloud First” policy requires agencies to adopt cloud services in preference to traditional IT systems. Cabinet has directed all public service agencies to contact the GCIO for advice and guidance when considering the use of any cloud service, and to follow a mandatory and uniform information management process issued by the GCIO.46 Agencies within the GCIO functional leadership mandate are required to follow the cloud risk assessment and endorsement process established by the GCIO. All public service agencies are expected to follow the process set out in this Cabinet direction.

There is no “cloud” classification system for data in New Zealand. Agency decision making currently relies on government security classifications in order to determine what data may be offshored (for storage and/or processing in cloud-based solutions). Government security classifications are essentially about the level of damage that would be done to the nation were the data to be exposed. No data above RESTRICTED is permitted to be held in a public cloud, whether it is hosted onshore or offshore. Data classified up to SENSITIVE can now be stored in AWS and Azure.

Procurement decisions on all cloud computing services (including cloud-based storage) are required to be made on a case-by-case basis after a proper risk assessment by agency chief executives with GCIO oversight, reflecting the importance of the GCIO as an adviser to agencies on cloud services. The current range of mandated processes and guidance available to agencies is set out set out online.

The risk assessment tools and guidance include:

The cloud risk assessment can inform, and can also be informed by, the Certification and Accreditation (C&A) process under the New Zealand Information Security Manual (NZISM) and by Privacy Impact Assessments.

The relevant agency’s Chief Executive or formal delegate is required to attest to the completeness and adequacy of the risk assessment that has been carried out before the agency can use the relevant cloud-based services. The completed cloud risk assessment tool and the sign-off (or “endorsement”) is then submitted to the GCIO.

Jurisdictional risk is inherent in any decision to store data offshore. It is effectively addressed by being selective about what jurisdiction data is transferred to, or by not transferring the data at all.

While agencies are typically considering security risk in the same context as jurisdictional risk, these are quite separate issues:

Accordingly, data location is key when assessing jurisdictional risk. Data location is not inherently key when assessing security risk, as the security risk will depend more on the capabilities and protections inherent in the relevant solution. Jurisdictional risk will also arise in the case of foreign-owned onshore providers (and is discussed in section 12 of this report).

The framework set out in “Managing Jurisdictional Risks for Public Cloud Services” requires agencies to carry out the following assessments:

On this definition of jurisdictional risk the government has identified a limited number of jurisdictions where New Zealand government data can be stored where the risk is “tolerable”. This guidance remains under review as those jurisdictions continue to update their laws. An example of this is the Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Assistance and Access) Act 2018 (Cth), which gave Australian law enforcement and intelligence agencies the ability to access data stored in Australian domiciled data centres, including data belonging to overseas governments.

All GIG respondents commented that jurisdictional risk is one factor in the risk assessment, to be considered alongside other risks including, for example, security, business continuity, cost, and latency. The emphasis that is placed on jurisdictional risk is necessarily a factor of the nature and importance of the data set in question.

While there were some inconsistencies amongst the GIG responses, it was generally acknowledged that using technical means to mitigate the risk of lawful access by foreign government and law enforcement agencies issues is not the solution. While this may solve the immediate access problem, it then creates a range of other problems – and could become quite a significant bilateral issue.

Viewed more broadly, jurisdictional risk also generates broader issues that agencies have to take into account for Māori (and New Zealanders generally) to have confidence that their data is protected after it is moved offshore. However, jurisdictional risk is currently being assessed by, and from the perspective of, the government. It appears that the level of tolerance for jurisdictional risk amongst Māori with interests or rights in relation to that data is not being routinely considered.

None of the Māori interviewees were intimately familiar with the GCDO’s “Managing Jurisdictional Risks for Public Cloud Services” – most did not know it existed. However, Māori interviewees were very clear that while offshore cloud-based storage solutions may be more secure than the domestic offerings from a technical point of view, the data is never going to be as secure from a sovereignty (Māori data sovereignty and New Zealand data sovereignty) perspective. Accordingly, offshoring data without “buy-in” or Māori involvement risks eroding trust and confidence in government decision making.

All Māori interviewees were critical of current government decision making processes and said that these must change.

One of the recurring themes in comments made by Māori interviewees on current government decision making processes was the lack of transparency. They observed that agencies are already making decisions about which data sets are too sensitive to go offshore, but that there is no visibility over what this looks like: “A lot of these decisions are made without any kind of consultation – not just Māori but other New Zealanders who want to understand the risks [of offshoring]”.

Those Māori interviewees who had seen decision making at play commented on decision making occurring in silos and the need for less “adhoc-ness”. One Māori interviewee, who has been contracted as a cultural adviser across different agencies, said he was not aware of any “one” decision making process.

Some Māori interviewees also observed that the primary driver for decisions to offshore government data were cost-effectiveness and security. They considered that New Zealand is being “led” by this lens, adding that financial cost is a very short-term consideration and that the government must also think about longer-term costs and benefits.

A number of Māori interviewees acknowledged that offshore public cloud providers are clearly better at security than the onshore service providers. However they also observed that agencies are not always doing their due diligence well – for example, understanding the full scope for data to be moved to, or accessed from, offshore locations (in addition to the primary site location) or for a service provider to access and retain data, particularly where the data is being processed by the service provider’s proprietary algorithms.

Similarly, various Māori interviewees pointed out that agencies have a clear lack of capacity and capability to act as stewards of Māori data. Two of the Māori interviewees noted that the highly publicised failure of the government’s approach to the 2018 census (i.e. the “digital-first” approach and the low turnout from Māori) demonstrates that the government does not have the requisite capacity/capability to act as a steward in relation to Māori data.53 Another Māori interviewee held the view that this plays into a wider problem of generally poor data governance in New Zealand.54 Agencies’ capacity and capability to act as stewards of Māori data is discussed further in section 9 of this report.

More fundamentally, Māori interviewees said that current decision making does not give Māori a say in relation to collection, use or access either: “It is very difficult for Māori at any level to be involved in the collection, and to exercise any rights in relation to data that has been collected about Māori, including accessing that information.”55 This is referred to further in section 8 of this report.

Some GIG respondents have also acknowledged the need for the government to establish and maintain the trust and confidence of Māori in connection with decisions to offshore government data, and have highlighted:

Some of the GIG respondents have paused their decision making in relation to offshoring certain data sets pending:

It was acknowledged that government agencies continue to grapple with how to apply a Te Ao Māori lens to the design, planning and execution of cloud storage adoption. It was suggested that this is largely due to a lack of capacity and capability within government, and the fact that current policy settings and frameworks are silent on how to achieve this.

Some agencies are utilising a range of complementary frameworks and tools in order to incorporate a Māori perspective when making broader decisions about:

There are also examples of organisations getting independent advice on the application of Te Tiriti in relation to particular programmes. One is the Health Quality Safety Commission, which recently decided against offshoring of data collected via the Patient Experience Survey.

Te Rau Whakatupu Māori, the Māori medium working group involved in the governance of the Ministry of Education’s Te Rito programme, recently discussed offshoring the hosting of learner information, and has taken the position that hosting data onshore is preferable.

An all-of-government Cloud Centre of Excellence (CCOE) is currently in the process of being established, led by the Digital Public Service branch (DPS) Te Kōtui Whitiwhiti of the Department of Internal Affairs. The intention of the CCOE is to better support agencies in the design, planning and execution of the adoption of cloud-based services. Increasingly, DPS is aware that the focus of agencies when conducting their risk assessments is not just on security and privacy, but also on the application of a Te Ao Māori lens. DPS has expressed an intention to develop an expanded toolkit to help agencies work through all three of these areas.

It was acknowledged that the government functional leads responsible for matters relating to cloud storage migration and data storage (i.e. the GCDO and GCDS)57 need to work together closely when engaging with Māori, particularly in those areas where they have joint or overlapping responsibility.

This section of the report focusses on legal considerations for agencies making decisions about where to store Māori data. It focusses in particular on Te Tiriti and the UNDRIP. However, it also considers the legal relevance of other instruments raised by Māori interviewees and agencies. These include He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni/The Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand (He Whakaputanga), and relationship agreements entered into between Māori and the Crown, often (but not always) in the context of the Treaty settlements process.

It is important to note at the outset that:

It is by now well known that the Māori and English texts of Te Tiriti (set out in full in Appendix 4) are not direct translations of each other, and the courts have accepted that they do not necessarily convey exactly the same meaning.60 For this reason, the courts, the Waitangi Tribunal and, in many cases, legislation often refer to the “principles of the Treaty of Waitangi”. Those principles have been the subject of considerable discussion in court judgments and Waitangi Tribunal reports. We set out from section 6 below the principles that we consider agencies may want to take into account when making decisions about the storage of Māori data. All arise against the background that Te Tiriti guarantees to Māori “te tino rangatiratanga” (absolute chieftainship/sovereignty) over (relevantly) “ratou taonga katoa” (all their treasures). We consider that Treaty principles may speak both to how those decisions are made, and what agencies may ultimately decide in respect of data storage.

Strictly speaking, the law remains that the rights conferred by Te Tiriti cannot be enforced in the Courts except in so far as a statutory recognition of the rights can be found.61 However, for present purposes, the significance of that strict position is limited for a number of reasons.

First, Te Tiriti is recognised in a number of statutes. This may be generally, or in more specific (and sometimes more limited) ways. To give just one example, a purpose of the Public Records Act 2005 is to “encourage the spirit of partnership and goodwill envisaged by the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi)”. To that end, and in order to “recognise and respect the Crown’s responsibility to take appropriate account of [Te Tiriti]”, the Act:

Secondly, Te Tiriti may be used as an aid to interpreting legislation even in the absence of a direct statutory reference.68 It can therefore colour agencies’ obligations under other statutes.

Thirdly, the Waitangi Tribunal has jurisdiction to inquire into Crown policies and practices to determine whether they are consistent with the principles of the Treaty. If they are not, and it considers that they are prejudicial to Māori, the Tribunal can make recommendations as to how to remedy the inconsistency. There is therefore a means by which the consistency of government action with Te Tiriti can be measured.

Finally, there is also a general responsibility under the Public Service Act 2020 for agencies to “[support] the Crown in its relationships with Māori under the Treaty of Waitangi (te Tiriti o Waitangi)”. While this responsibility is owed to the Minister responsible for the relevant agency, it reflects the broader position that, in general, the Crown may be presumed (morally, if not legally) to want to honour its commitments under Te Tiriti and its principles. All of this means that Te Tiriti and its principles do provide a useful framework to guide Crown action in relation to Māori rights and interests in Māori data.

We have heard concerns expressed that if data is to be moved offshore, it will be held in a jurisdiction where Te Tiriti does not apply. It is true that Te Tiriti does not apply to overseas companies. Equally, however, it does not apply to companies based in New Zealand. In either case, the position is the same: Te Tiriti obligations fall on the Crown, and the Crown must ensure that it is able to meet those obligations if it decides to delegate or outsource its responsibilities to third parties. As the Waitangi Tribunal said in the Ngawha Geothermal Resource Report (in the context of the control of natural resources):

"If the Crown chooses to so delegate it must do so in terms which ensure that its Treaty duty ofprotection is fulfilled."

As discussed earlier, however, overseas governments and law enforcement agencies may have rights to access data stored in their jurisdiction (and, in some circumstances, to data held by companies from their jurisdictions who store data in New Zealand). The exercise of those rights would not be constrained by Te Tiriti.

There is no single or definitive statement of the principles of the Treaty. Instead, they must be gleaned from decisions of the courts and the Waitangi Tribunal, and from the text of Te Tiriti itself. Set out below are the principles that could be thought to be most relevant to decision making in this space, together with a brief discussion in relation to each.

Te Tiriti gives the Crown a right of kāwanatanga (the right to govern), but reserves to Māori tino rangatiratanga. The Waitangi Tribunal has explained the relationship between these concepts in this way:

"The Treaty of Waitangi was based on a fundamental exchange of kāwanatanga, or the right of the Crown to govern and make laws for the country, in exchange for the right of Māori to exercise tino rangatiratanga over their land, resources and people. Finding the appropriate balance between governance for all New Zealanders and protection of the Treaty rights of Māori is complex and cannot be applied generally to any given situation. We must consider the circumstances of each case, what is at stake, and the options available for resolution. In any case, the Crown’s right of kāwanatanga is not an unfettered authority. The guarantee of rangatiratanga requires the Crown to acknowledge Māori control over their tikanga, and to manage their own affairs in a way that aligns with their customs and values."

In its Wai 262 report, the Waitangi Tribunal explained the concept of tino rangatiratanga in relation to taonga as follows:

"Through the Treaty, the Crown won the right to enact laws and make policies. That proposition has been accepted time and again by the courts, as well as this Tribunal. It could hardly be otherwise in New Zealand’s robust democracy. But that right is not absolute. It was – and remains – qualified by the promises solemnly made to Māori in the Treaty, the nation’s pre-eminent constitutional document. Like any constitutional promise, those made in the Treaty cannot be set aside without agreement, except after careful consideration and as a last resort.

Of these promises, the most important in this context is the guarantee to protect the tino rangatiratanga of iwi and hapū over their ‘taonga katoa’ – that is, the highest chieftainship over all their treasured things. Most speakers of Māori would render tino rangatiratanga, in its Treaty context, as a right to autonomy or self-government. The courts have found that the tino rangatiratanga of iwi and hapū is entitled to active protection by the Crown."

The Tribunal went on to say that what tino rangatiratanga can or should entail will depend on the circumstances of the case. It recognised different situations in which greater or lesser decision making authority should rest with Māori:

"In accordance with Treaty principle tino rangatiratanga must be protected to the greatest extent practicable, but – like kāwanatanga – it is not absolute. After 170 years during which Māori have been socially, culturally, and economically swamped, it will no longer be possible to deliver tino rangatiratanga in the sense of full authority over all taonga Māori. It will, however, be possible to deliver full authority in some areas. That will either be because the absolute importance of the taonga interest in question means other interests must take second place or, conversely, because competing interests are not sufficiently important to outweigh the constitutionally protected taonga interest.

Where ‘full authority’ tino rangatiratanga is no longer practicable, lesser options may be. It may, for example, be possible to share decision making in relation to taonga that are important to the culture and identity of iwi or hapū. And where shared decision making is no longer possible, it should always be open to Māori to influence the decisions of others where those decisions affect their taonga. This might be done through, for example, formal consultation mechanisms.

Just what tino rangatiratanga can or should entail will now depend on the particular circumstances of the case. But law and policy makers must always keep firmly in mind the crucial point that the tino rangatiratanga guarantee is a constitutional guarantee of the highest order, and not lightly to be diluted or put to one side."

On this basis, there are “levels” of tino rangatiratanga that may be exercised: from full authority, to shared decision making, to influence and consultation. In some cases, full authority for Māori may be required because of the importance of a particular taonga interest. Where that is not practicable, shared decision making might be appropriate. If that is not possible either, then there should nevertheless be an opportunity for Māori to influence the way that decisions that affect their taonga are made.

The Waitangi Tribunal in the Tū Mai Te Rangi! report explained that the principle of partnership arises out of the exchange of kāwanatanga and rangatiratanga, and “describes how the Crown and Māori were to relate to each other under the Treaty as two peoples living in one country”. It said:

"This relationship is founded on good faith and respect. It requires both parties to act reasonably towards one another, with each party acknowledging the needs and interests of the other. This requires co-operation, compromise and the will to achieve mutual benefit. It also means respect for each partner’s spheres of authority."

Similar sentiments have been expressed by the Courts, which have said that the principle of partnership:

In considering the principle of partnership, the Waitangi Tribunal has made clear that Te Tiriti envisages that Māori and the Crown are equals. Accordingly, Māori interests are not simply one factor to be considered among many other priorities. Rather, “Māori autonomy is pivotal to the Treaty and to the partnership concept it entails”.

In the Lands case, Richardson J explained that:

"The responsibility of one Treaty partner to act in good faith fairly and reasonably towards the other puts the onus on a partner, here the Crown, when acting within its sphere to make an informed decision, that is a decision where it is sufficiently informed as to the relevant facts and law to be able to say it has had proper regard to the impact of the principles of the Treaty."

Similarly, in the Tū Mai Te Rangi! report, the Tribunal said:

"We accept the guarantee of rangatiratanga means ‘it is for Māori to say what their interests are, and to articulate how they might best be protected’."

Accordingly, the Crown needs to ensure that its policy processes are sufficiently informed by Māori knowledge and opinions to make good on its obligations under Te Tiriti. However, this does not necessarily require a full consultation exercise in respect of every decision. In some cases, the Crown may already be in possession of sufficient information “for it to act consistently with the principles of the Treaty without any specific consultation”. There is judicial recognition that “wide-ranging consultations could hold up the processes of Government in a way contrary to the principles of the Treaty”. The Waitangi Tribunal has similarly recognised that “[t]he degree of consultation required in any given instance may … vary depending on the extent of consultation necessary for the Crown to make an informed decision”. In line with this, we consider that it may be possible for Māori and the Crown to work together to develop agreements or guidelines for the Crown to apply to data sets that are within Crown control.

Where the Crown does need further information, however, the Tribunal’s acceptance that “it is for Māori to say what their interests are, and to articulate how they might best be protected”85 has implications for how that consultation should be carried out. If Māori know what their interests are (which will depend on them knowing what Māori data agencies hold) and how they might best be protected, it makes sense to involve them early on in the decision making process, rather than to consult them on what has already been decided is a good idea. This was a theme echoed by some Māori interviewees.

As explained in a series of court decisions and Waitangi Tribunal reports, the Crown’s duties under the Treaty are not merely passive, but extend to active protection of Māori interests. In its Manukau Report, the Waitangi Tribunal explained:

"The Treaty of Waitangi obliges the Crown not only to recognise the Māori interests specified in the Treaty but actively to protect them. The possessory guarantees of the second article must be read in conjunction with the Preamble (where the Crown is “anxious to protect” the tribes against the envisaged exigencies of emigration) and the Third Article where a “royal protection” is conferred. It follows that the omission to provide that protection is as much a breach of the Treaty as a positive act that removes those rights."

The duty of active protection applies not only to lands and waters (the subject of discussion in the Lands case), but also to the taonga protected by Article II of the Treaty.

As is the case with the duties discussed above, the duty of active protection is context dependent. In the Ngawha Geothermal Resource Report, the Tribunal said that:

"The duty of active protection applies to all the interests guaranteed to Māori under article 2 of the Treaty. While not confined to natural and cultural resources, these interests are of primary importance. There are several important elements including the need to ensure that the degree of protection to be given to Māori resources will depend upon the nature and value of the resource. In the case of a very highly valued rare and irreplaceable taonga of great spiritual and physical importance to Māori, the Crown is under an obligation to ensure its protection (save in very exceptional circumstances) for so long as Māori wish it to be so protected. … The value attached to such a taonga is essentially a matter for Māori to determine."

In the context of Māori data, active protection would seem to us to require at the very least that the data is held securely and that it is protected for future generations. It is likely also to require appropriate restrictions on use and access (intentional and unintentional), in line with requirements of Māori in relation to the data. What more may be required would, we consider, depend on the particular data in question, and its significance and importance to Māori.91

The principle of options is that, as Te Tiriti partners, Māori have the right “to choose their social and cultural path”. It protects the rights of Māori “to continue their way of life according to their indigenous traditions and worldview while participating in British society and culture, as they wish”. It is derived from the twin guarantees under Te Tiriti of tino rangatiratanga and the rights and privileges of British citizenship.

The final Treaty principle worth mentioning is the right to development. The Waitangi Tribunal has recognised that there is a right to development inherent in the rights guaranteed by Te Tiriti. It includes the right of Māori to develop their social and economic status and institutions of self-government. We consider that this right is relevant in the present context because of the power of data for development. It speaks especially to the importance of the accessibility of data to Māori, as such access can facilitate the exercise their right to development.

The Crown’s obligations under Te Tiriti are especially high where it is making decisions or taking actions in respect of taonga. The Waitangi Tribunal has defined taonga as “things valued or treasured”. It has said:

"They may include those things which give sustenance and those things which support taonga. Generally speaking the classification of taonga is determined by the use to which they are put and/or their significance as possessions. They are imbued with tapu (an aura of protection) to protect them from wrongful use, theft or desecration."

To similar effect, the courts have recognised taonga as a “highly prized property or treasure”.

Neither the courts nor the Waitangi Tribunal have considered whether data can be a taonga. However, it is clear that the concept of taonga covers intangible things, such as mātauranga Māori. There is no obvious conceptual barrier to Māori data being a taonga as that concept has been understood by the Waitangi Tribunal and the courts.

We consider that, by analogy with the Wai 262 claim, it is reasonably clear that at least some Māori data can be taonga. In the Wai 262 report, the Waitangi Tribunal drew a distinction between “taonga works” and “taonga-derived works”. Taonga works are those that are in their entirety an expression of mātauranga Māori, relate to or invoke ancestral connections (whakapapa), and contain or reflect traditional narratives or stories. They possess mauri (life force) and have living kaitiaki (guardians) in accordance with tikanga Māori. Taonga-derived works, by contrast, are those that derive their inspiration from mātauranga Māori or a taonga work, but do not relate to or invoke ancestral connections (whakapapa), nor contain or reflect traditional narratives or stories in any direct way. The Tribunal considered that greater protection was appropriate for taonga works than taonga-derived works. Similarly, the Tribunal considered that whether a species is a taonga species “can be tested”:

"Taonga species have mātauranga Māori in relation to them. They have whakapapa able to be recited by tohunga (expert practitioners). Certain iwi or hapū will say that they are kaitiaki in respect of the species. Their tohunga will be able to say what events in the history of the community led to that kaitiaki status, and what obligations this creates for them. In essence, a taonga species will have kōrero tuku iho, or inherited learnings, the existence and credibility of which can be tested."

By analogy, we consider that data that is significant and important to Māori or Māori culture could readily be found to be deserving of active protection by the Crown and something in respect of which there should be a significant place in decision making for Māori. Examples of such data could include data that is related to or invokes ancestral connections, data about the natural environment or indigenous species, or significant data about people (such as data about health). On the other hand, the Crown’s obligations in respect of data accumulated in the context of the ordinary activities of government (tax information or traffic infringement information, for example) may be lower. On this approach, data could be classified on a spectrum, with (say as agreed in a co-designed framework) different obligations applying to different types of Māori data. This is akin to the approach suggested in a recent article by Māui Hudson et al.

This approach is also consistent with the Waitangi Tribunal’s approach in other contexts, where it has accepted that what is required of the Crown in relation to particular taonga is fact dependent. In its report on the National Freshwater and Geothermal Resources claim, the Tribunal took the view that there was a need for a “principled regime” for environmental management, which it envisaged would entail a sliding scale:

"… We accept the Crown’s argument that it is required to govern in the interests of the nation and the best interests of the environment, and that it must balance many interests in doing so. We also note, as the Tribunal has done many times in the past, that Māori are the Crown’s Treaty partner and not just one interest group among many. Nor can Māori Treaty rights be balanced out of existence. Rather, the Crown’s balancing of interests must be fair and must comply with Treaty principles. We agree with the findings of the Wai 262 report, as put to us by the Crown …, that a principled regime for environmental management must be established so as to determine what degree of priority should be accorded the Māori interest in any one case. We also agree that a sliding scale is necessary: sometimes kaitiaki control will be appropriate, sometimes a partnership arrangement, and sometimes kaitiaki influence will suffice, depending upon the balance of interests (including the interest of the taonga itself)."

Ultimately, we consider that in ascertaining whether data is a taonga, the nature and value of the taonga, and how it should be protected, agencies are best guided by Māori. In the Ngawha Geothermal Resources Report, the Tribunal explained that consultation would be particularly important where a taonga was at issue because:

"The Crown obligation actively to protect Māori Treaty rights cannot be fulfilled in the absence of a full appreciation of the nature of the taonga including its spiritual and cultural dimensions. This can only be gained from those having rangatiratanga over the taonga."

As has been foreshadowed, we consider that, as the law currently stands in New Zealand, it is not helpful to speak of the ownership of data (Māori or otherwise).

From a Western legal perspective, ownership rights may arise in relation to some data – but only to the extent that the data qualifies for protection under the law of intellectual property, and in particular the law of copyright. This will often not be the case, especially in relation to raw or unstructured data.

Further, while the English text of Te Tiriti guarantees to Māori the “full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries and other properties”, the Māori text guarantees tino rangatiratanga over “o ratou taonga katoa” (all the treasured things of Māori tribes (“ngā hapu”) and all Māori people (“nga tangata katoa”)). In relation to mātauranga Māori, the Waitangi Tribunal has taken the view that tino rangatiratanga is not equivalent to ownership, and that what is more important is authority and control:

"… In short, the Māori text implies that control is more important than possession. In the context ofvtaonga works and mātauranga Māori, we think that approach is entirely appropriate.

We consider therefore that the English-language guarantee of exclusive and undisturbed possession of ‘their … properties’ lacks the flexibility necessary to address Māori interests in taonga works and mātauranga Māori. We prefer the more accommodating, if less precise, language of the Māori text’s recognition of Māori rangatiratanga over ‘o ratou taonga katoa’ – all of their treasured things.

In the context of modern IP law, the principle of tino rangatiratanga applied to ‘o ratou taonga katoa’ must mean simply that the legal framework should deliver to Māori a reasonable measure of control over the use of taonga works and mātauranga Māori. Such a standard is obvious and easily stated, but the more difficult question is how far that rangatiratanga authority should go and what is reasonable in this complex subject. …"

The Wai 262 Tribunal reached a similar conclusion when it was considering the relationship of Māori with the natural environment:

"The final point to be made about the Treaty is that although the English text guarantees rights in the nature of ownership, the Māori text uses the language of control – tino rangatiratanga – not ownership. Equally, kaitiakitanga – the obligation side of rangatiratanga – does not require ownership. In reality, therefore, the kaitiakitanga debate is not about who owns the taonga, but who exercises control over it. …

In the end, it is the degree of control exercised by Māori and their influence in decision making that needs to be resolved in a principled way by using the concept of kaitiakitanga. The exact degree of control accorded to Māori as kaitiaki will differ widely in different circumstances, and cannot be determined in a generic way."

We consider that the same approach is appropriate in relation to data. That is particularly so given that there are many reasons why agencies may need to collect, or receive, data, including data in relation to Māori, to allow the Crown to carry out its good government obligations. Attempting to ascertain the ownership of such data is unlikely to be productive. The real question is what the Crown needs to do to discharge its obligations under the principle of tino rangatiratanga.

That said, we do not discount the possibility that concepts of ownership may become relevant as part of the broader work being carried out in relation to Māori data governance.

Overseas, indigenous people have asserted governance over data relating to themselves by reference to concepts of ownership. A notable example is the First Nations Principles of OCAP, by which First Nations assert ownership, control, access and possession of First Nations data. The principle of “ownership” is as follows:

"Ownership refers to the relationship of First Nations to their cultural knowledge, data, and information. This principle states that a community or group owns information collectively in the same way that an individual owns his or her personal information."

While the OCAP principles go beyond data storage (dealing also with information creation and the research process) and are said to be “First Nations-specific, … not applicable as an Aboriginal principle”, we note that they have been referred to by Te Mana Raraunga in its Charter as a potential way to conceptualise rangatiratanga over data.

He Whakaputanga is a declaration preceding Te Tiriti consisting of four articles in which a number of rangatira asserted rangatiratanga, kīngitanga (dominion), and mana over their “Wenua Rangatira” under the title Te Wakaminenga o ngā Hapū o Nu Tireni (the sacred Confederation of Tribes of New Zealand). He Whakaputanga generally receives much less legal attention than Te Tiriti. In part, that is likely to be because it has not been accepted as an aid to the interpretation of contemporary statutes. It is not usually seen as a constraint on Crown action. However, it may be relevant insofar as it is a further assertion of tino rangatiratanga and Māori decision making authority.

In addition to their obligations arising from Te Tiriti, agencies may also want to consider the UNDRIP in decision making concerning Māori data.

The New Zealand government announced its support for the UNDRIP in April 2010. While the UNDRIP is not directly enforceable in New Zealand domestic law, the key point is, again, that the Crown may be presumed to want to comply with it. Indeed, in 2019 the government agreed that Te Minita Whanaketanga Māori (the Minister for Māori Development) would lead a process to develop a national plan of action/strategy on New Zealand’s progress towards the objectives of the UNDRIP. Additionally, the Waitangi Tribunal has taken the view that “the UNDRIP articles are relevant to the interpretation of the principles of the Treaty”, and that it is “relevant to the manner in which the principles of the Treaty should be observed by Crown officials”. That was particularly the case, it said, where its articles “provide specific guidance as to how the Crown should be interacting with Māori or recognising their interests”.

In this context, we consider that the following articles of the UNDRIP are particularly relevant:

Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

Indigenous peoples, in exercising their right to self-determination, have the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs, as well as ways and means for financing their autonomous functions.

Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures, as well as to maintain and develop their own indigenous decision making institutions.

States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them.